|

| Igor Morski |

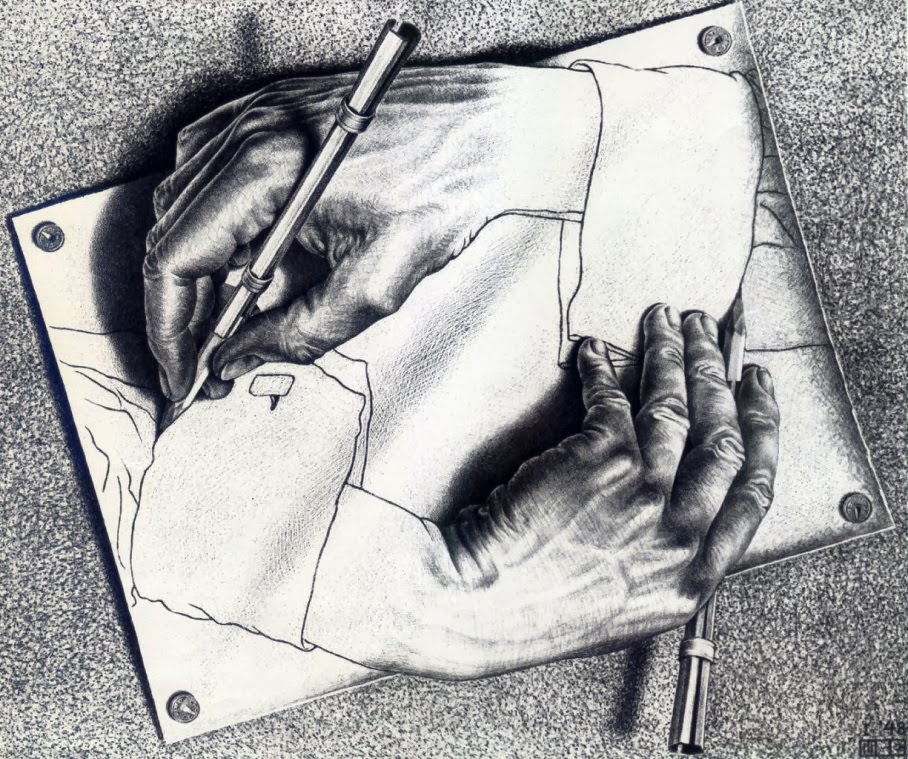

The search for a Self in the enaction perspective, considering worlds of consciousness and experience without ground analyzed according to the Abhidharma Buddhist tradition, has to answer in a circular way to the question "how can there seem to be a coherent self when there is none?". The answer returns to the recursive circularity between science (in particular cognitive sciences) and experience without falling in the abyss of Nihilism:

WORLDS WITHOUT GROUND

Laying Down a Path in Walking

Science and Experience in Circulation

In the preface we announced that the theme of this book would be the circulation between cognitive science and human experience. In this final chapter we wish to situate this circulation within a wider contemporary context. In particular we wish to consider some of the ethical dimensions of groundlessness in relation to the concern with nihilism that is typical of much post-Nietzschean thought. This is not the place to consider the many points that animate current North American and European discussions; our concern, rather, is to indicate how we see our project in relation to these discussions and to suggest further directions for investigation.

The back-and-forth communication between cognitive science and experience that we have explored can be envisioned as a circle. The circle begins with the experience of the cognitive scientist, a human being who can conceive of a mind operating without a self. This becomes embodied in a scientific theory. Emboldened by the theory, one can discover, with a disciplined, mindful approach to experience, that although there is constant struggle to maintain a self, there is no actual self in experience. The natural scientific inquisitiveness of the mind then queries, But how can there seem to be a coherent self when there is none? For an answer one can tum to mechanisms such as emergence and societies of mind. Ideally that could lead one to penetrate further into the causal relationships in one's experience, seeing the causes and effects of ego grasping and enabling one to begin to relax the struggle of ego grasping. As perceptions, relationships, and the activity of mind expand into awareness, one might have insight into the codependent lack of ultimate foundations either for one's mind or for its objects, the world. The inquisitive scientist then asks, How can we imagine, embodied in a mechanism, that relation of codependence between mind and world? The mechanism that we have created (the embodied metaphor of groundlessness) is that of enactive cognition, with its image of structural coupling through a history of natural drift. Ideally such an image can influence the scientific society and the larger society, loosening the hold of both objectivism and subjectivism and encouraging further communication between science and experience, experience and science.

The logic of this back-and-forth circle exemplified the fundamental circularity in the mind of the reflective scientist. The fundamental axis of this circulation is the embodiment of experience and cognition. It should be recalled that embodiment in our sense, as for Merleau-Ponty, encompasses both the body as a lived , experiential structure and the body as the context or milieu of cognitive mechanisms. Thus in the communication we have portrayed in this book between cognitive science and the tradition of mind fullness/awareness, we have systematically juxtaposed the descriptions of experience taken from mind fullness/awareness practice with descriptions of cognitive architecture taken from cognitive science.

Like Merleau-Ponty, we have emphasized that a proper appreciation of this twofold sense of embodiment provides a middle way or entre-deux between the extremes of absolutism and nihilism. Both of these two extremes can be found in contemporary cognitive science. The absolutist extreme is easy to find, for despite other differences, the varieties of cognitive realism share the conviction that cognition is grounded in the representation of a pregiven world by a pregiven subject. The nihilist extreme is less apparent, but we have seen how it arises when cognitive science uncovers the nonunity of the self yet ignores the possibility of a transformative approach to human experience.

So far we have devoted less attention to this nihilist extreme, but it is in fact far more indicative of our contemporary cultural situation. Thus in the humanities - in art, literature , and philosophy - the growing awareness of groundlessness has taken form not through a confrontation with objectivism but rather with nihilism , skepticism, and extreme relativism. Indeed, this concern with nihilism is typical of late-twentieth-century life. Its visible manifestations are the increasing fragmentation of life , the revival of and continuing adherence to a variety of religious and political dogmatisms, and a pervasive yet intangible feeling of anxiety, which writers such as Milan Kundera in The Unbearable Lightness of Being depict so vividly.

It is for this reason (and because nihilism and objectivism are actually deeply connected) that we turn to consider in more detail the nihilistic extreme. We have reserved this issue until now because it is both general and far reaching. Our discussion must accordingly become more equally concerned with the ethical dimension of groundlessness than it has been so far. In the final section of this chapter we will be more explicit about this ethical dimension. Before doing so, however, we wish to examine in more detail the nihilist extreme.

Nihilism and the Need for Planetary Thinking

The back-and-forth communication between cognitive science and experience that we have explored can be envisioned as a circle. The circle begins with the experience of the cognitive scientist, a human being who can conceive of a mind operating without a self. This becomes embodied in a scientific theory. Emboldened by the theory, one can discover, with a disciplined, mindful approach to experience, that although there is constant struggle to maintain a self, there is no actual self in experience. The natural scientific inquisitiveness of the mind then queries, But how can there seem to be a coherent self when there is none? For an answer one can tum to mechanisms such as emergence and societies of mind. Ideally that could lead one to penetrate further into the causal relationships in one's experience, seeing the causes and effects of ego grasping and enabling one to begin to relax the struggle of ego grasping. As perceptions, relationships, and the activity of mind expand into awareness, one might have insight into the codependent lack of ultimate foundations either for one's mind or for its objects, the world. The inquisitive scientist then asks, How can we imagine, embodied in a mechanism, that relation of codependence between mind and world? The mechanism that we have created (the embodied metaphor of groundlessness) is that of enactive cognition, with its image of structural coupling through a history of natural drift. Ideally such an image can influence the scientific society and the larger society, loosening the hold of both objectivism and subjectivism and encouraging further communication between science and experience, experience and science.

The logic of this back-and-forth circle exemplified the fundamental circularity in the mind of the reflective scientist. The fundamental axis of this circulation is the embodiment of experience and cognition. It should be recalled that embodiment in our sense, as for Merleau-Ponty, encompasses both the body as a lived , experiential structure and the body as the context or milieu of cognitive mechanisms. Thus in the communication we have portrayed in this book between cognitive science and the tradition of mind fullness/awareness, we have systematically juxtaposed the descriptions of experience taken from mind fullness/awareness practice with descriptions of cognitive architecture taken from cognitive science.

Like Merleau-Ponty, we have emphasized that a proper appreciation of this twofold sense of embodiment provides a middle way or entre-deux between the extremes of absolutism and nihilism. Both of these two extremes can be found in contemporary cognitive science. The absolutist extreme is easy to find, for despite other differences, the varieties of cognitive realism share the conviction that cognition is grounded in the representation of a pregiven world by a pregiven subject. The nihilist extreme is less apparent, but we have seen how it arises when cognitive science uncovers the nonunity of the self yet ignores the possibility of a transformative approach to human experience.

So far we have devoted less attention to this nihilist extreme, but it is in fact far more indicative of our contemporary cultural situation. Thus in the humanities - in art, literature , and philosophy - the growing awareness of groundlessness has taken form not through a confrontation with objectivism but rather with nihilism , skepticism, and extreme relativism. Indeed, this concern with nihilism is typical of late-twentieth-century life. Its visible manifestations are the increasing fragmentation of life , the revival of and continuing adherence to a variety of religious and political dogmatisms, and a pervasive yet intangible feeling of anxiety, which writers such as Milan Kundera in The Unbearable Lightness of Being depict so vividly.

It is for this reason (and because nihilism and objectivism are actually deeply connected) that we turn to consider in more detail the nihilistic extreme. We have reserved this issue until now because it is both general and far reaching. Our discussion must accordingly become more equally concerned with the ethical dimension of groundlessness than it has been so far. In the final section of this chapter we will be more explicit about this ethical dimension. Before doing so, however, we wish to examine in more detail the nihilist extreme.

Nihilism and the Need for Planetary Thinking

Let us begin not by attempting to engage nihilism directly but rather by asking how nihilism arises. Where and at what point does the nihilist tendency first manifest itself?

We have been led to face groundlessness or the lack of stable foundations in both enactive cognitive science and in the mindful, open-ended approach to experience. In both settings we began naively but were forced to suspend our deep-seated conviction that the world is grounded independently of embodied perceptual and cognitive capacities. This deep-seated conviction is the motivation for objectivism-even in its most refined philosophical forms. Nihilism, however, is in a sense based on no analogous conviction, for it arises initially in reaction to the loss of faith in objectivism. Nihilism can, of course, be cultivated to a point where it takes on a life of its own, but in its first moment its form is one of response. Thus we can already see that nihilism is in fact deeply linked to objectivism, for nihilism is an extreme response to the collapse of what had seemed to provide a sure and absolute reference point.

We have already provided an example of this link between objectivism and nihilism when we examined the discovery within cognitive science of selfless minds. This deep and profound discovery requires the cognitive scientist to acknowledge that consciousness and selfidentity do not provide the ground or foundation for cognitive processes; yet she feels that we do believe, and must continue to believe, in an efficacious self. The usual response of the cognitive scientist is to ignore the experiential aspect when she does science and ignore the scientific discovery when she leads her life. As a result, the nonexistence of a self that would answer to our objectivist representations is typically confused with the nonexistence of the relative (practical) self altogether. Indeed, without the resources provided by a progressive approach to experience, there is little choice but to respond to the collapse of an objective self (objectivism) by asserting the objective nonexistence of the self (nihilism).

This response indicates that objectivism and nihilism, despite their apparent differences, are deeply connected-indeed the actual source of nihilism is objectivism. We have already discussed how the basis of objectivism is to be found in our habitual tendency to grasp after regularities that are stable but ungrounded. In fact, nihilism too arises from this grasping mind. Thus faced with the discovery of groundlessness, we nonetheless continue to grasp after a ground because we have not relinquished the deep-seated reflex to grasp that lies at the root of objectivism. This reflex is so strong that the absence of a solid ground is immediately reified into the objectivist abyss. This act of reification performed by the grasping mind is the root of nihilism. The mode of repudiation or denial that is characteristic of nihilism is actually a very subtle and refined form of objectivism: the mere absence of an objective ground is reified into an objective groundlessness that might continue to serve as an ultimate reference point. Thus although we have been speaking of objectivism and nihlism as opposed extremes with differing consequences, they ultimately share a common basis in the grasping mind.

An appreciation of the common source of objectivism and nihilism lies at the heart of the philosophy and practice of the middle way in Buddhism. For this reason, we are simply misinformed when we assume that concern with nihilism is a modem phenomenon of Greco-European origin. To appreciate the resources offered by these other traditions, however, we must not lose sight of the specificity of our present situation. Whereas in Buddhism, as anywhere else, there is always the danger of individuals experiencing nihilism (losing heart, as it is called in Buddhism) or of commentators straying into nihilistic errors of interpretation, nihilism has never become full blown or embodied in societal institutions.

Today nihilism is a tangible issue not only for our Western culture but for the planet as a whole. And yet as we have seen throughout this book, the groundlessness of the middle way in Mahayana Buddhism offers considerable resources for human experience in our present scientific culture. The mere recognition of this fact should indicate that the imaginative geography of "West" and "East" is no longer appropriate for the tasks we face today. Although we can begin from the premises and concerns of our own tradition, we need no longer proceed in ignorance of other traditions, especially of those that continually strived to distinguish rigorously between the groundlessness of nihilism and the groundlessness of the middle way.

Unlike Richard Rorty, then, we are not inspired in our attempt to face the issue of groundlessness and nihilism by the ideal of simply "continuing the conversation of the West." Instead, our project throughout this book owes far more to Martin Heidegger's invocation of "planetary thinking." As Heidegger wrote in The Question of Being,

We have been led to face groundlessness or the lack of stable foundations in both enactive cognitive science and in the mindful, open-ended approach to experience. In both settings we began naively but were forced to suspend our deep-seated conviction that the world is grounded independently of embodied perceptual and cognitive capacities. This deep-seated conviction is the motivation for objectivism-even in its most refined philosophical forms. Nihilism, however, is in a sense based on no analogous conviction, for it arises initially in reaction to the loss of faith in objectivism. Nihilism can, of course, be cultivated to a point where it takes on a life of its own, but in its first moment its form is one of response. Thus we can already see that nihilism is in fact deeply linked to objectivism, for nihilism is an extreme response to the collapse of what had seemed to provide a sure and absolute reference point.

We have already provided an example of this link between objectivism and nihilism when we examined the discovery within cognitive science of selfless minds. This deep and profound discovery requires the cognitive scientist to acknowledge that consciousness and selfidentity do not provide the ground or foundation for cognitive processes; yet she feels that we do believe, and must continue to believe, in an efficacious self. The usual response of the cognitive scientist is to ignore the experiential aspect when she does science and ignore the scientific discovery when she leads her life. As a result, the nonexistence of a self that would answer to our objectivist representations is typically confused with the nonexistence of the relative (practical) self altogether. Indeed, without the resources provided by a progressive approach to experience, there is little choice but to respond to the collapse of an objective self (objectivism) by asserting the objective nonexistence of the self (nihilism).

This response indicates that objectivism and nihilism, despite their apparent differences, are deeply connected-indeed the actual source of nihilism is objectivism. We have already discussed how the basis of objectivism is to be found in our habitual tendency to grasp after regularities that are stable but ungrounded. In fact, nihilism too arises from this grasping mind. Thus faced with the discovery of groundlessness, we nonetheless continue to grasp after a ground because we have not relinquished the deep-seated reflex to grasp that lies at the root of objectivism. This reflex is so strong that the absence of a solid ground is immediately reified into the objectivist abyss. This act of reification performed by the grasping mind is the root of nihilism. The mode of repudiation or denial that is characteristic of nihilism is actually a very subtle and refined form of objectivism: the mere absence of an objective ground is reified into an objective groundlessness that might continue to serve as an ultimate reference point. Thus although we have been speaking of objectivism and nihlism as opposed extremes with differing consequences, they ultimately share a common basis in the grasping mind.

An appreciation of the common source of objectivism and nihilism lies at the heart of the philosophy and practice of the middle way in Buddhism. For this reason, we are simply misinformed when we assume that concern with nihilism is a modem phenomenon of Greco-European origin. To appreciate the resources offered by these other traditions, however, we must not lose sight of the specificity of our present situation. Whereas in Buddhism, as anywhere else, there is always the danger of individuals experiencing nihilism (losing heart, as it is called in Buddhism) or of commentators straying into nihilistic errors of interpretation, nihilism has never become full blown or embodied in societal institutions.

Today nihilism is a tangible issue not only for our Western culture but for the planet as a whole. And yet as we have seen throughout this book, the groundlessness of the middle way in Mahayana Buddhism offers considerable resources for human experience in our present scientific culture. The mere recognition of this fact should indicate that the imaginative geography of "West" and "East" is no longer appropriate for the tasks we face today. Although we can begin from the premises and concerns of our own tradition, we need no longer proceed in ignorance of other traditions, especially of those that continually strived to distinguish rigorously between the groundlessness of nihilism and the groundlessness of the middle way.

Unlike Richard Rorty, then, we are not inspired in our attempt to face the issue of groundlessness and nihilism by the ideal of simply "continuing the conversation of the West." Instead, our project throughout this book owes far more to Martin Heidegger's invocation of "planetary thinking." As Heidegger wrote in The Question of Being,

We are obliged not to give up the effort to practice planetary thinking along a stretch of the road, be it ever so short. Here too no prophetic talents and demeanor are needed to realize that there are in store for planetary building encounters for which the participants are by no means equal today. This is equally true of the European and of the East Asiatic languages and, above all, for the area of a possible conversation between them. Neither one of the two is able by itself to open up this area and to establish it.Our guiding metaphor is that a path exists only in walking, and our conviction has been that as a first step we must face the issue of groundlessness in our scientific culture and learn to embody that groundlessness in the openness of sunyata. One of the central figures of twentieth-century Japanese philosophy, Nishitani Keiji, has in fact made precisely this claim. Nishitani is exemplary for us because he was not only raised and personally immersed in the Zen tradition of mindfulness/awareness but was also one of Heidegger's students and so is thoroughly familiar with European thought in general and Heidegger's invocation of planetary thinking in particular. Nishitani's endeavor to develop a truly planetary form of philosophical yet embodied, progressive reflection is impressive.