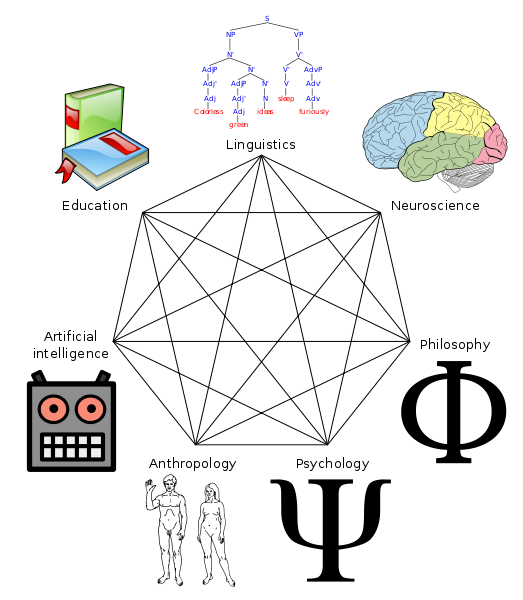

The cognitivist hypothesis to the study of mind and consciousness has found historically wide application in a number of fields:

Manifestations of Cognitivism

Cognitivism in Artificial Intelligence

The manifestations of cognitivism are nowhere more visible than in artificial intelligence (AI), which is the literal construal of the cognitivist hypothesis. Over the years many interesting theoretical advances and technological applications have been made within this orientation, such as expert systems, robotics, and image processing. These results have been widely publicized, and so we need not digress to provide specific examples here.

Because of wider implications, however, it is worth noting that AI and its cognitivist basis reached a dramatic climax in Japan's ICOT Fifth Generation Program. For the first time since the war there is a national plan involving the efforts of industry, government, and universities, launched in 1981. The core of this program is a cognitive device capable of understanding human language and of writing its own programs when presented with a task by an untrained user. Not surprisingly, the heart of the ICOT program was the development of a series of interfaces of knowledge representation and problem solving based on PROLOG, a high-level programming language for predicate logic. The ICOT program has triggered immediate responses from Europe and the United States, and there is little question that this is a major commercial concern and engineering battlefield. (It is also worth noting that the Japanese goverment has launched in 1990 the Sixth Generation Program based on connectionist models.) Although it is only one example, the ICOT program is a major illustration ofthe inseparability of science and technology in the study of cognition and of the effects that this marriage has on the public at large.

The cognitivist hypothesis has in AI its most literal construal. The complementary endeavor is the study of natural, biologically implemented cognitive systems, especially humans. Here, too, computationally characterizable representations have been the main explanatory tool. Mental representations are taken to be occurrences of a formal system, and the mind's activity is what gives these representations their attitudinal color-beliefs, desires, intentions, etc. Here, therefore, unlike AI, we find an interest in what the natural cognitive systems are really like, and it is assumed that their cognitive representations are about something for the system; they are said to be intentional in the sense indicated here.

Cognitivism and the Brain

Another equally important effect of cognitivism is the way it has shaped current views about the brain. Even though in theory the symbolic level of cognitivism is compatible with many views about the brain, in practice almost all of neurobiology (and its huge body of empirical evidence) has become permeated with the cognitivist, information-processing perspective. More often than not, the origins and assumptions of this perspective are not even questioned.

The exemplar of this approach is the celebrated studies of the visual cortex, an area of the brain where one can easily detect electrical responses from neurons when the animal is presented with a visual image. It was reported early on that it was possible to classify cortical neurons, such as feature detectors, responding to certain attributes of the object being presented-its orientation, contrast, velocity, color, and so on. In line with the cognitivist hypothesis, these results have been seen as the biological basis for the notion that the brain picks up visual information from the retina through the feature-specific neurons in the cortex, and the information is then passed on to later stages in the brain for further processing (conceptual categorization, memory associations, and eventually action).

In its most extreme form, this view of the brain is expressed in Barlow's "grandmother cell" doctrine, where there is a correspondence between concepts (such as the concept someone has of her grandmother) or percepts and specific neurons. (This is equivalent - to AI detectors and labeled lines.) This extreme view is waning in popularity now, but the basic idea that the brain is an information processing device that responds selectively to features of the environment remains as the dominant core of modem neuroscience and in the public's understanding.

Cognitivism in Psychology

Psychology is the discipline that most people assume to be the study of mind. Psychology predates cognitive science and cognitivism and is not coextensive with either of them. What influence has cognitivism had on psychology? To understand something of this, we need some historical background in psychology.

We have already mentioned introspectionism and its differences from mindfulness meditation. It may be that when anyone first thinks to inquire about the mind, there are a limited number of possibilities of how to proceed, and turning to one's own mind is one of the universal strategies that will occur. This track, developed by the. meditative traditions of India, was aborted for psychology in the West when the nineteenth-century introspectionists, lacking a method of mindfulness, tried to treat the mind as an external object, with disastrous results for interobserver agreement. The breakdown of introspectionism into noncommensurable, warring laboratories left experimental psychology with a profound distrust of self-knowledge as a legitimate procedure in psychology. Introspectionism was replaced by the dominant school of behaviorism.

One obvious alternative to looking inward to the mind is to look outward at behavior; we even have the folk saying, "Actions speak louder than words." Behaviorism was particularly compatible with the early twentieth-century positivist zeitgeist of disembodied objectivism in science, for it eliminated mind entirely from its psychology. According to behaviorism, although one could objectively observe inputs to the organism (stimuli) and outputs (behavior) and could investigate the lawful relationships between inputs and outputs over time, the organism itself (both its mind and its biological body) was a black box that was methodologically unapproachable by behavioral science (hence no rules, no symbols, no computations). Behaviorism completely dominated North American experimental psychology from the 1920s until fairly recently.

The first signs of a postbehaviorist experimental cognitive psychology began to appear in the late 195Os. The trick of these early researchers who were still, strictly speaking, positivist, was to find experimental means for defining and measuring the effect of a given forbidden mentalistic phenomenon. Let us take mental images as an example.

A mental image is undisputably in the black box for a behaviorist; it is not publicly observable, so one cannot have observer agreement about it. Researchers, however, gradually devised demonstrations of the pragmatic effects of mental images. Instructing an experimental subject to hold a mental image during a signal detection task lowers the accuracy of the detection, and, furthermore, this effect is modality specific (a visual image interferes more in a visual detection task than an auditory task, and vice versa). Such experiments legitimate imagery even in behaviorist terminology-imagery is a powerful intervening variable. Furthermore, experiments began to explore the behavior of mental images in themselves, often showing that they had properties like those of perceptual images. In delightfully ingenious experiments, Kosslyn showed that mental visual images appear to be scanned in real time, and Shepard and Metzler showed that mental images appear to be rotated in real time just as perceptual visual images are. Studies of other formerly mentalistic (now called cognitive) phenomena began to be performed in perception, memory, language, problem solving, concepts, and decision making.

What influence did cognitivism have on this emerging experimental investigation of the mind? Interestingly, the initial effect of cognitivism on psychology was extremely liberating. The computer metaphor of the mind could be used to formulate experimental hypotheses or even to legitimate one's theory simply by programming it. Although the programs were almost entirely cognitivist (psychological processes were modeled in terms of explicit rules, symbols, and representations), the overall effect was to breach the constraints of behaviorist orthodoxy and admit into psychology long-suppressed, commonsense understanding of the mind. For example, developmental psycholinguistics could now explore openly the idea that children learn the vocabulary and grammar of their language not as reinforced, paired associates but as hypotheses about correct adult speech that develop with their cognitive capacities and experience. Motivation could be understood as more than hours of deprivation; one could now talk of cognitive representations of goals and plans. The social system was not just a complex stimulus; it could be modeled in the mind as representations of scripts and social schemas. One coulq speak of the human information processor as a lay scientist, testing hypotheses and making mistakes. In short, the introduction of the computer metaphor in a very general, albeit implicitly cognitivist, sense into cognitive psychology allowed an explosion of commonsense theory and its operationalization into computer models and human research.

Strict cognitivism in its explicit form, on the other hand, places strong constraints on theory and has generated primarily philosophical debate. Let us return to mental imagery as an example. In cognitivism, mental imagery, like any other cognitive phenomenon, can be no more than the manipulation of symbols by computational rules. Yet Shepard's and Kosslyn's experiments have demonstrated that mental images perform in a continuous fashion in real time, very like visual perception. Does this refute cognitivism? A hard-line cognitivist, such as Pylyshyn, argues that images are simply subjective epiphenomena (as they were for behaviorism) of more fundamental symbolic computations. Attempting to bridge the rift between data and cognitivist theory, Kosslyn has formulated a model by which images are generated in the mind by the same rules that generate images in computer displays: the interaction of languagelike operations and picturelike operations together generate the internal eye. One current view of the imagery debate is that since, at best, the imagery research demonstrates the similarity of imagery to perception, this simply points us to the need for a viable account of perception.

Cognitivism and Psychoanalysis

We stated earlier that psychoanalytic theory had mirrored much of the development of cognitive science. In fact, psychoanalysis was explicitly cognitivist in its inception. Freud attended Brentano's course in Vienna, as did Husserl, and he fully endorsed the representational and intentional view of the mind. For Freud, nothing could affect behavior unless it were mediated by a representation, even an instinct. “An instinct can never be an object of consciousness—only the idea that represents the instinct. Even in the unconscious, moreover, it can only be represented by the idea.” Within this framework, Freud's great discovery was that not all representations were accessible to consciousness; he never seemed to doubt that the unconscious, for all that it might operate on a different symbol system than the conscious, was fully symbolic, fully intentional, and fully representational.

Freud's descriptions of mental structures and processes are sufficiently general and metaphorical that they have proved translatable (with arguable degrees of loss of meaning) into the language of other psychological systems. In the Anglo-American world, one extreme was Dollard and Miller's hotly contested retheorizing of Freudian discoveries in terms of behaviorist-based learning theory. More relevant for us was Erdelyi's rather placidly accepted (perhaps because of Freud's preexisting cognitivist "metaphysics") translation into cognitivist-based information-processing language. For example, Freud's concept of repression/censorship becomes, in cognitivist terms, the matching of information from a perception or idea to a criterion level for acceptable accounts of anxiety: if it is above the criterion, it goes to a stop-processing/accessing information box, from whence it is shunted back to the unconscious; if below the criterion, it is allowed into the preconscious and, perhaps, then into the conscious. After another criterion match in the decision tree, it is either allowed into behavior or suppressed. Does such a description add anything to Freud? It certainly serves to translate such notions as the Freudian unconscious into what is taken to be a "scientific" currency of the day. It is also fair to say that many contemporary post-Freudian theorists in Europe-such as Jacques Lacan-would disagree: such theorizing misses the central spirit of the psychoanalytic journey-to move beyond the trap of representations, including those about the unconscious.

It is presently fashionable to say that Freud "decentered" the self; what he actually did was to divide the self into several basic selves. Freud was not a strict cognitivist in the Pylyshyn sense: the unconscious had the same type of representations as the conscious, all of which could, at least theoretically, become, or have been, conscious. Modem strict cognitivism has a far more radical and alienating view of unconscious processing. It is to this issue that we now tum as we discuss the meaning of cognitivism for our experience.

.jpg)