It was a short one-paragraph item in the morning edition. A friend rang me up and read it to me. Nothing special. Something a rookie reporter fresh out of college might've written for practice.

The date, a street corner, a person driving a truck, a pedestrian, a casualty, an investigation of possible negligence.

Sounded like one of those poems on the inner flap of a magazine.

"Where's the funeral?" I asked.

"You got me," he said. "Did she even have family?"

Of course she had a family.

I called the police department to track down her family's address and telephone number, after which I gave them a call to get details of the funeral.

Her family lived in an old quarter of Tokyo. I got out my map and marked the block in red. There were subway and train and bus lines everywhere, overlapping like some misshapen spiderweb, the whole area a maze of narrow streets and drainage canals.

The day of the funeral, I took a streetcar from Waseda. I got off near the end of the line. The map proved about as helpful as a globe would have been. I ended up buying pack after pack of cigarettes, asking directions each time.

It was a wood-frame house with a brown board fence around it. A small yard, with an abandoned ceramic brazier filled with standing rainwater. The ground was dark and damp.

She'd left home when she was sixteen. Which may have been the reason why the funeral was so somber. Only family present, nearly everyone older. It was presided over by her older brother, barely thirty, or maybe it was her brother-in-law.

Her father, a shortish man in his mid-fifties, wore a black armband of mourning. He stood by the entrance and scarcely moved. Reminded me of a street washed clean after a downpour.

On leaving, I lowered my head in silence, and he lowered his head in return, without a word.

I met her in autumn nine years ago, when I was twenty and she was seventeen.

There was a small coffee shop near the university where I hung out with friends. It wasn't much of anything, but it offered certain constants: hard rock and bad coffee.

She'd always be sitting in the same spot, elbows planted on the table, reading. With her glasses--which resembled orthodontia--and skinny hands, she seemed somehow endearing. Always her coffee would be cold, always her ashtray full of cigarette butts.

The only thing that changed was the book. One time it'd be Mickey Spillane, another time Kenzaburo Oe, another time Allen Ginsberg. Didn't matter what it was, as long as it was a book. The students who drifted in and out of the place would lend her books, and she'd read them clean through, cover to cover. Devour them, like so many ears of corn. In those days, people lent out books as a matter of course, so she never wanted for anything to read.

Those were the days of the Doors, the Stones, the Byrds, Deep Purple, and the Moody Blues. The air was alive, even as everything seemed poised on the verge of collapse, waiting for a push.

She and I would trade books, talk endlessly, drink cheap whiskey, engage in unremarkable sex. You know, the stuff of everyday. Meanwhile, the curtain was creaking down on the shambles of the sixties.

I forget her name.

I could pull out the obituary, but what difference would it make now. I've forgotten her name.

Suppose I meet up with old friends and mid-swing the conversation turns to her. No one ever remembers her name either. Say, back then there was this girl who'd sleep with anyone, you know, what's-her-face, the name escapes me, but I slept with her lots of times, wonder what she's doing now, be funny to run into her on the street.

"Back then, there was this girl who'd sleep with anyone." That's her name.

Of course, strictly speaking, she didn't sleep with just anyone. She had standards.

Still, the fact of the matter is, as any cursory examination of the evidence would suffice to show, that she was quite willing to sleep with almost any guy.

Once, and only once, I asked her about these standards of hers.

"Well, if you must know . . . ," she began. A pensive thirty seconds went by. "It's not like anybody will do. Sometimes the whole idea turns me off. But you know, maybe I want to find out about a lot of different people. Or maybe that's how my world comes together for me."

"By sleeping with someone?"

"Uh-huh."

It was my turn to think things over.

"So tell me, has it helped you make sense of things?"

"A little," she said.

From the winter through the summer I hardly saw her. The university was blockaded and shut down on several occasions, and in any case, I was going through some personal problems of my own.

When I visited the coffee shop again the next autumn, the clientele had completely changed, and she was the only face I recognized. Hard rock was playing as before, but the excitement in the air had vanished. Only she and the bad coffee were the same. I plunked down in the chair opposite her, and we talked about the old crowd.

Most of the guys had dropped out, one had committed suicide, one had buried his tracks. Talk like that.

"What've you been up to this past year?" she asked me.

"Different things," I said.

"Wiser for it?"

"A little."

That night, I slept with her for the first time.

About her background I know almost nothing. What I do know, someone may have told me; maybe it was she herself when we were in bed together. Her first year of high school she had a big falling out with her father and flew the coop (and high school too). I'm pretty sure that's the story. Exactly where she lived, what she did to get by, nobody knew.

She would sit in some rock-music café all day long, drink cup after cup of coffee, chain-smoke, and leaf through books, waiting for someone to come along to foot her coffee and cigarette bills (no mean sum for us types in those days), then typically end up sleeping with the guy.

There. That's everything I know about her.

From the autumn of that year on into the spring of the next, once a week on Tuesday nights, she'd drop in at my apartment outside Mitaka. She'd put away whatever simple dinner I cooked, fill my ashtrays, and have sex with me with the radio tuned full blast to an FEN rock program. Waking up Wednesday mornings, we'd go for a walk through the woods to the ICU campus and have lunch in the dining hall. In the afternoon, we'd have a weak cup of coffee in the student lounge, and if the weather was good, we'd stretch out on the grass and gaze up at the sky.

Our Wednesday afternoon picnic, she called it.

"Everytime we come here, I feel like we're on a picnic."

"Really? A picnic?"

"Well, the grounds go on and on, everyone looks so happy . . ."

She sat up and fumbled through a few matches before lighting a cigarette.

"The sun climbs high in the sky, then starts down. People come, then go. The time breezes by. That's like a picnic, isn't it?"

I was twenty-one at the time, about to turn twenty-two. No prospect of graduating soon, and yet no reason to quit school. Caught in the most curiously depressing circumstances. For months I'd been stuck, unable to take one step in any new direction. The world kept moving on; I alone was at a standstill. In the autumn, everything took on a desolate cast, the colors swiftly fading before my eyes. The sunlight, the smell of the grass, the faintest patter of rain, everything got on my nerves.

How many times did I dream of catching a train at night? Always the same dream. A nightliner stuffy with cigarette smoke and toilet stink. So crowded there was hardly standing room. The seats all caked with vomit. It was all I could do to get up and leave the train at the station. But it was not a station at all. Only an open field, with not a house light anywhere. No stationmaster, no clock, no timetable, no nothing--so went the dream.

I still remember that eerie afternoon. The twenty-fifth of November. Gingko leaves brought down by heavy rains had turned the footpaths into dry riverbeds of gold. She and I were out for a walk, hands in our pockets. Not a sound to be heard except for the crunch of the leaves under our feet and the piercing cries of the birds.

"Just what is it you're brooding over?" she blurted out all of a sudden.

"Nothing really," I said.

She kept walking a bit before sitting down by the side of the path and taking a drag on her cigarette.

"You always have bad dreams?"

"I often have bad dreams. Generally, trauma about vending machines eating my change."

She laughed and put her hand on my knee, but then took it away again.

"You don't want to talk about it, do you?"

"Not today. I'm having trouble talking."

She flicked her half-smoked cigarette to the dirt and carefully ground it out with her shoe. "You can't bring yourself to say what you'd really like to say, isn't that what you mean?"

"I don't know," I said.

Two birds flew off from nearby and were swallowed up into the cloudless sky. We watched them until they were out of sight. Then she began drawing indecipherable patterns in the dirt with a twig.

"Sometimes I get real lonely sleeping with you."

"I'm sorry I make you feel that way," I said.

"It's not your fault. It's not like you're thinking of some other girl when we're having sex. What difference would that make anyway? It's just that--" She stopped mid-sentence and slowly drew three straight lines on the ground. "Oh, I don't know."

"You know, I never meant to shut you out," I broke in after a moment. "I don't understand what gets into me. I'm trying my damnedest to figure it out. I don't want to blow things out of proportion, but I don't want to pretend they're not there. It takes time."

"How much time?"

"Who knows? Maybe a year, maybe ten."

She tossed the twig to the ground and stood up, brushing the dry bits of grass from her coat. "Ten years? C'mon, isn't that like forever?"

"Maybe," I said.

We walked through the woods to the ICU campus, sat down in the student lounge, and munched on hot dogs. It was two in the afternoon, and Yukio Mishima's picture kept flashing on the lounge TV. The volume control was broken so we could hardly make out what was being said, but it didn't matter to us one way or the other. A student got up on a chair and tried fooling with the volume, but eventually he gave up and wandered off.

"I want you," I said.

"Okay," she said.

So we thrust our hands back into our coat pockets and slowly walked back to the apartment.

I woke up to find her sobbing softly, her slender body trembling under the covers. I turned on the heater and checked the clock. Two in the morning. A startlingly white moon shone in the middle of the sky.

I waited for her to stop crying before putting the kettle on for tea. One teabag for the both of us. No sugar, no lemon, just plain hot tea. Then lighting up two cigarettes, I handed one to her. She inhaled and spat out the smoke, three times in rapid succession, before she broke down coughing.

"Tell me, have you ever thought of killing me?" she asked.

"You?"

"Yeah."

"Why're you asking me such a thing?"

Her cigarette still at her lips, she rubbed her eyelid with her fingertip.

"No special reason."

"No, never," I said.

"Honest?"

"Honest. Why would I want to kill you?"

"Oh, I guess you're right," she said. "I thought for a second there that maybe it wouldn't be so bad to get murdered by someone. Like when I'm sound asleep."

"I'm afraid I'm not the killer type."

"Oh?"

"As far as I know."

She laughed. She put her cigarette out, drank down the rest of her tea, then lit up again.

"I'm going to live to be twenty-five," she said, "then die."

July, eight years later, she was dead at twenty-six.

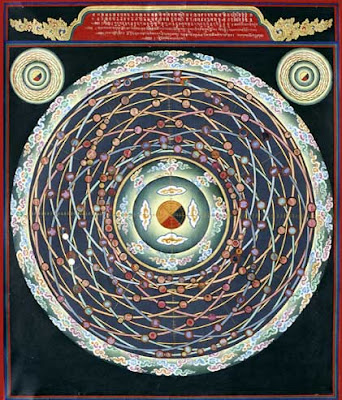

The structural coupling of the particles with mass with the Anderson-Higgs field, and more generally the exchange of virtual particles from a particle with any other, and vice versa, well represents the metaphor of the Indra Net of about 2600 years ago.

The structural coupling of the particles with mass with the Anderson-Higgs field, and more generally the exchange of virtual particles from a particle with any other, and vice versa, well represents the metaphor of the Indra Net of about 2600 years ago.